Charlie Hebdo

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

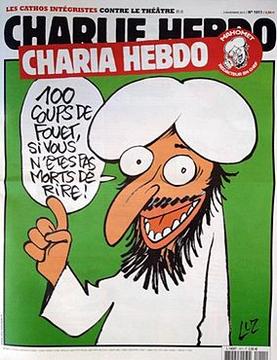

Logo of the weekly Charlie Hebdo

| |

| Type | Weekly satirical news magazine |

|---|---|

| Format | Magazine |

| Founded | 1970,[1] 1992 |

| Political alignment | Left-wing |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

| Circulation | 45,000 |

| ISSN | 1240-0068 |

| Website | charliehebdo.fr |

Charlie Hebdo (French pronunciation: [ʃaʁli ɛbdo]; French for Weekly Charlie) is a French satirical weekly newspaper, featuring cartoons, reports, polemics, and jokes. Irreverent and stridently non-conformist in tone, the publication is strongly antireligious[2] and left-wing, publishing articles on the extreme right, Catholicism, Islam, Judaism, politics,culture, etc. According to its former editor, Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier), the magazine's editorial viewpoint reflects "all components of left wing pluralism, and even abstainers".[3]

It first appeared from 1969 to 1981; it folded, but was resurrected in 1992. Charb was the most recent editor, holding the post from 2009 until his death in the attack on the magazine's offices in 2015. His predecessors wereFrançois Cavanna (1969–1981) and Philippe Val (1992–2009).

The magazine is published every Wednesday, with special editions issued on an unscheduled basis.

On 7 January 2015, during the weekly editorial board meeting, suspected Islamic terrorists gunned down and killed 10 journalists and two police officers at the newspaper's Paris office.[4][5]

Contents

[hide]History

In 1960, Georges "Professeur Choron" Bernier and François Cavanna launched a monthly magazine entitled Hara-Kiri.[6] Choron acted as the director of publication and Cavanna as its editor. Eventually Cavanna gathered together a team which included Roland Topor, Fred, Jean-Marc Reiser, Georges Wolinski, Gébé (fr), and Cabu. After an early reader's letter accused them of being "dumb and nasty" ("bête et méchant"), the phrase became an official slogan for the magazine and made it into everyday language in France.

1969–1981

In 1969, the Hara-Kiri team decided to produce a weekly publication – on top of the existing monthly magazine – which would focus more on current affairs. This was launched in February as Hara-Kiri Hebdo and renamed L'Hebdo Hara-Kiriin May of the same year.[citation needed] ('Hebdo' is short for 'hebdomadaire' – 'weekly')

In November 1970, the former French president Charles de Gaulle died in his home village of Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, eight days after a disaster in a nightclub, the Club Cinq-Sept fire caused the death of 146 people. The magazine released a cover spoofing the popular press's coverage of this disaster, headlined "Tragic Ball at Colombey, one dead."[6] As a result, the journal was once more banned, this time by the Minister of the Interior.

In order to sidestep the ban, the team decided to change its title, and used Charlie Hebdo.[1] The new name was derived from a monthly comics magazine called Charlie Mensuel (Charlie Monthly), which had been started by Bernier and Delfeil de Ton in 1968. Charlie took its name from Charlie Brown, the lead character of Peanuts – one of the comics originally published in Charlie Mensuel – and was also an inside joke about Charles de Gaulle.[7] In December 1981, publication ceased.

1992–2010

In 1991, Gébé, Cabu and others were reunited to work for La Grosse Bertha, a new weekly magazine resemblingCharlie created in reaction to the First Gulf War and edited by comic singer Philippe Val. However, the following year, Val clashed with the publisher, who wanted apolitical mischief, and was fired. Gébé and Cabu walked out with him and decided to launch their own paper again. The three called upon Cavanna, Delfeil de Ton and Wolinski, requesting their help and input. After much searching for a new name, the obvious idea of resurrecting Charlie-Hebdo was agreed on. The new magazine was owned by Val, Gébé, Cabu and singer Renaud Séchan. Val was editor, Gébé artistic director.

The publication of the new Charlie Hebdo began in July 1992 amidst much publicity. The first issue under the new publication sold 100,000 copies. Choron, who had fallen out with his former colleagues, tried to restart a weekly Hara-Kiri, but its publication was short-lived. Choron died in January 2005.

In 2000, journalist Mona Chollet was sacked after she had protested against a Philippe Val article which called Palestinians "non-civilized".[8] In 2004, following the death of Gébé, Val succeeded him as director of the publication, while still holding his position as editor.

Controversy arose over the publication's edition of 9 February 2006. Under the title "Mahomet débordé par les intégristes" ("Muhammad overwhelmed by fundamentalists"), the front page showed a cartoon of a weeping Prophet Muhammad saying "C'est dur d'être aimé par des cons" ("it's hard being loved by jerks"). The newspaper reprinted the twelve cartoons of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy and added some of their own. Compared to a regular circulation of 100,000 sold copies, this edition enjoyed great commercial success. 160,000 copies were sold and another 150,000 were in print later that day.

In response, French President Jacques Chirac condemned "overt provocations" which could inflame passions. "Anything that can hurt the convictions of someone else, in particular religious convictions, should be avoided", Chirac said. The Grand Mosque, the Muslim World League and the Union of French Islamic Organisations (UOIF) sued, claiming the cartoon edition included racist cartoons.[9] A later edition contained a statement by a group of 12 writers warning against Islamism.[10]

The suit by the Grand Mosque and the UOIF reached the courts in February 2007. Publisher Philippe Val contended "It is racist to imagine that they can't understand a joke" but Francis Szpiner, the lawyer for the Grand Mosque, explained the suit: "Two of those caricatures make a link between Muslims and Muslim terrorists. That has a name and it's called racism."[11]

Future president Nicolas Sarkozy sent a letter to be read in court expressing his support for the ancient French tradition of satire.[12] François Bayrou and future president François Hollande also expressed their support for freedom of expression. The French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM) criticized the expression of these sentiments, claiming they were politicizing a court case.[13]

On 22 March 2007, executive editor Philippe Val was acquitted by the court.[14] The court followed the state attorney's reasoning that two of the three cartoons were not an attack on Islam, but on Muslim terrorists, and that the third cartoon with Mohammed with a bomb in his turban should be seen in the context of the magazine in question which attacked religious fundamentalism.

In 2008, controversy broke over a column by veteran cartoonist Siné which led to accusations of antisemitism and Siné's sacking by Val. Siné sued the newspaper for unfair dismissal and Charlie Hebdo was sentenced to pay him €90,000 in damages.[15] Siné launched a rival paper called Siné Hebdo which later became Siné Mensuel. Charlie Hebdo launched its Internet site, after years of reluctance[citation needed] from Val.

In 2009, Philippe Val resigned after being appointed director of France Inter, a public radio station to which he has contributed since the early 1990s. His functions were split between two cartoonists, Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier) and Riss (Laurent Sourisseau). Val gave away his shares in 2011.[citation needed]

2011

The paper's controversial 3 November 2011 issue, renamed "Charia Hebdo" (a reference to Sharia law) and "guest-edited" by Muhammad, depicted Muhammad saying: "100 lashes of the whip if you don't die laughing."

November 2011 attacks

In the early hours of 2 November 2011, the newspaper's office in the 20th arrondissement[16] was fire-bombed and its website hacked. The attacks were presumed linked to its decision to rename a special edition "Charia Hebdo", with the Islamic Prophet Mohammed listed as the "editor-in-chief".[17] The cover, featuring a cartoon of Mohammed by Luz (Renald Luzier), had circulated on social media for a couple of days.

Charb was quoted by AP stating that the attack might have been carried out by "stupid people who don't know what Islam is" and that they are "idiots who betray their own religion". Mohammed Moussaoui, head of the French Council of the Muslim Faith, said his organisation deplores "the very mocking tone of the paper toward Islam and its prophet but reaffirms with force its total opposition to all acts and all forms of violence."[18] François Fillon, the prime minister, andClaude Guéant, the interior minister, voiced support for Charlie Hebdo,[16] as did feminist writer Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who criticised calls for self-censorship.[19]

2012

In September 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammed, some of which feature nude caricatures of him.[20][21] Given that this came days after a series of attacks on U.S. embassies in the Middle East, purportedly in response to the anti-Islamic film Innocence of Muslims, the French government decided to increase security at certain French embassies, as well as to close the French embassies, consulates, cultural centers, and international schools in about 20 Muslim countries.[22] In addition, riot police surrounded the offices of the magazine to protect against possible attacks.[21][23][24]

Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius criticised the magazine's decision, saying, "In France, there is a principle of freedom of expression, which should not be undermined. In the present context, given this absurd video that has been aired, strong emotions have been awakened in many Muslim countries. Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?"[25] However, the newspaper's editor defended publication of the cartoons, saying, "We do caricatures of everyone, and above all every week, and when we do it with the Prophet, it's called provocation."[26][27]

January 2015 attack

Main article: Charlie Hebdo shooting

| This section documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. (January 2015) |

On 7 January 2015, at least two gunmen opened fire at the Paris office of Charlie Hebdo, killing at least 12, and wounding 11, 4 seriously.[4][28] Staff cartoonists Charb, Cabu, Honoré, Tignous, and Wolinski[29] along with economistBernard Maris, and two police officers standing guard at the magazine were all killed.[30][31][32][33] President François Hollande described it as a "terrorist attack of the most extreme barbarity".[34

No comments:

Post a Comment